[ad_1]

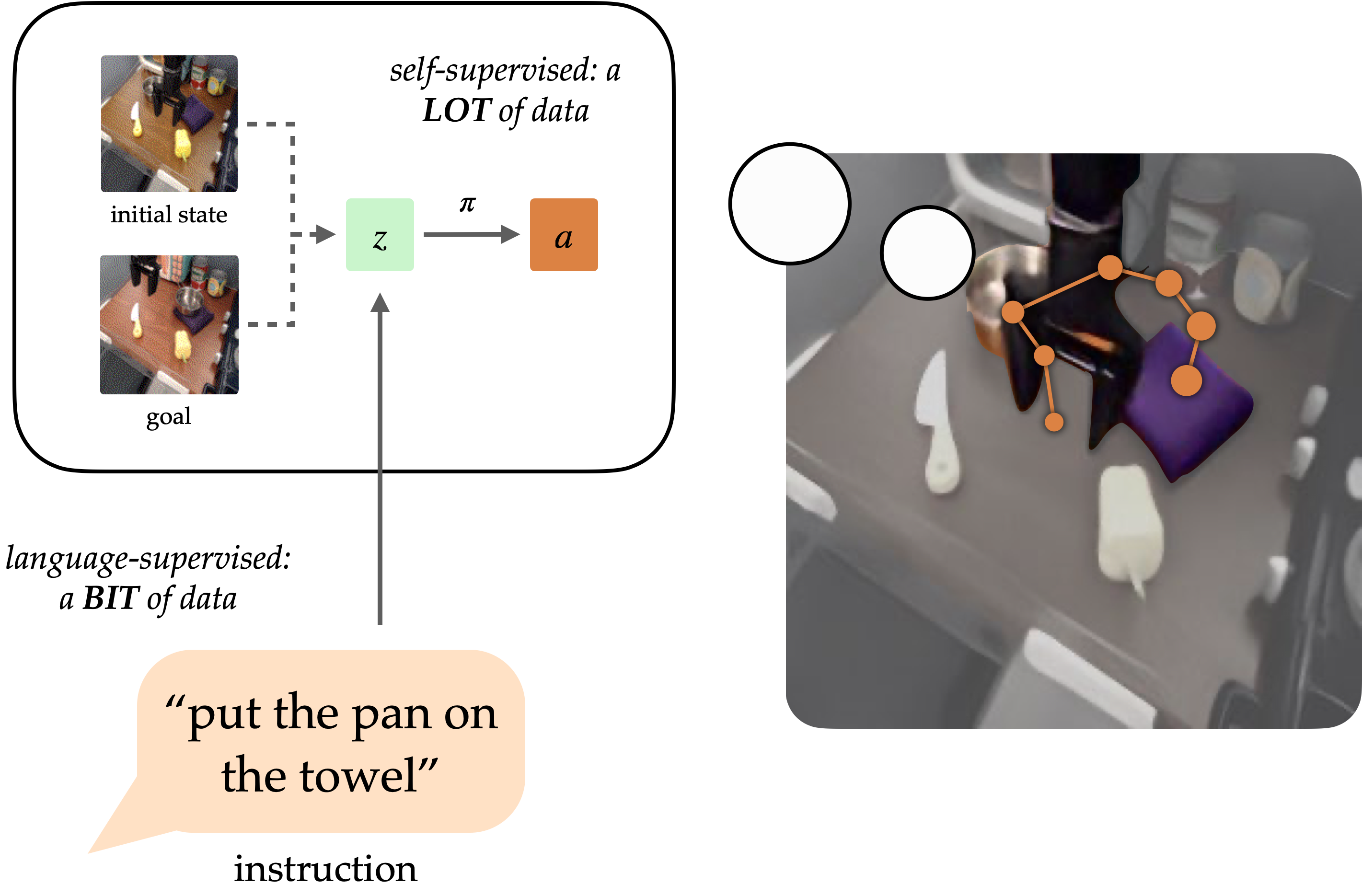

A longstanding goal of the field of robot learning has been to create generalist agents that can perform tasks for humans. Natural language has the potential to be an easy-to-use interface for humans to specify arbitrary tasks, but it is difficult to train robots to follow language instructions. Approaches like language-conditioned behavioral cloning (LCBC) train policies to directly imitate expert actions conditioned on language, but require humans to annotate all training trajectories and generalize poorly across scenes and behaviors. Meanwhile, recent goal-conditioned approaches perform much better at general manipulation tasks, but do not enable easy task specification for human operators. How can we reconcile the ease of specifying tasks through LCBC-like approaches with the performance improvements of goal-conditioned learning?

Conceptually, an instruction-following robot requires two capabilities. It needs to ground the language instruction in the physical environment, and then be able to carry out a sequence of actions to complete the intended task. These capabilities do not need to be learned end-to-end from human-annotated trajectories alone, but can instead be learned separately from the appropriate data sources. Vision-language data from non-robot sources can help learn language grounding with generalization to diverse instructions and visual scenes. Meanwhile, unlabeled robot trajectories can be used to train a robot to reach specific goal states, even when they are not associated with language instructions.

Conditioning on visual goals (i.e. goal images) provides complementary benefits for policy learning. As a form of task specification, goals are desirable for scaling because they can be freely generated hindsight relabeling (any state reached along a trajectory can be a goal). This allows policies to be trained via goal-conditioned behavioral cloning (GCBC) on large amounts of unannotated and unstructured trajectory data, including data collected autonomously by the robot itself. Goals are also easier to ground since, as images, they can be directly compared pixel-by-pixel with other states.

However, goals are less intuitive for human users than natural language. In most cases, it is easier for a user to describe the task they want performed than it is to provide a goal image, which would likely require performing the task anyways to generate the image. By exposing a language interface for goal-conditioned policies, we can combine the strengths of both goal- and language- task specification to enable generalist robots that can be easily commanded. Our method, discussed below, exposes such an interface to generalize to diverse instructions and scenes using vision-language data, and improve its physical skills by digesting large unstructured robot datasets.

Goal Representations for Instruction Following

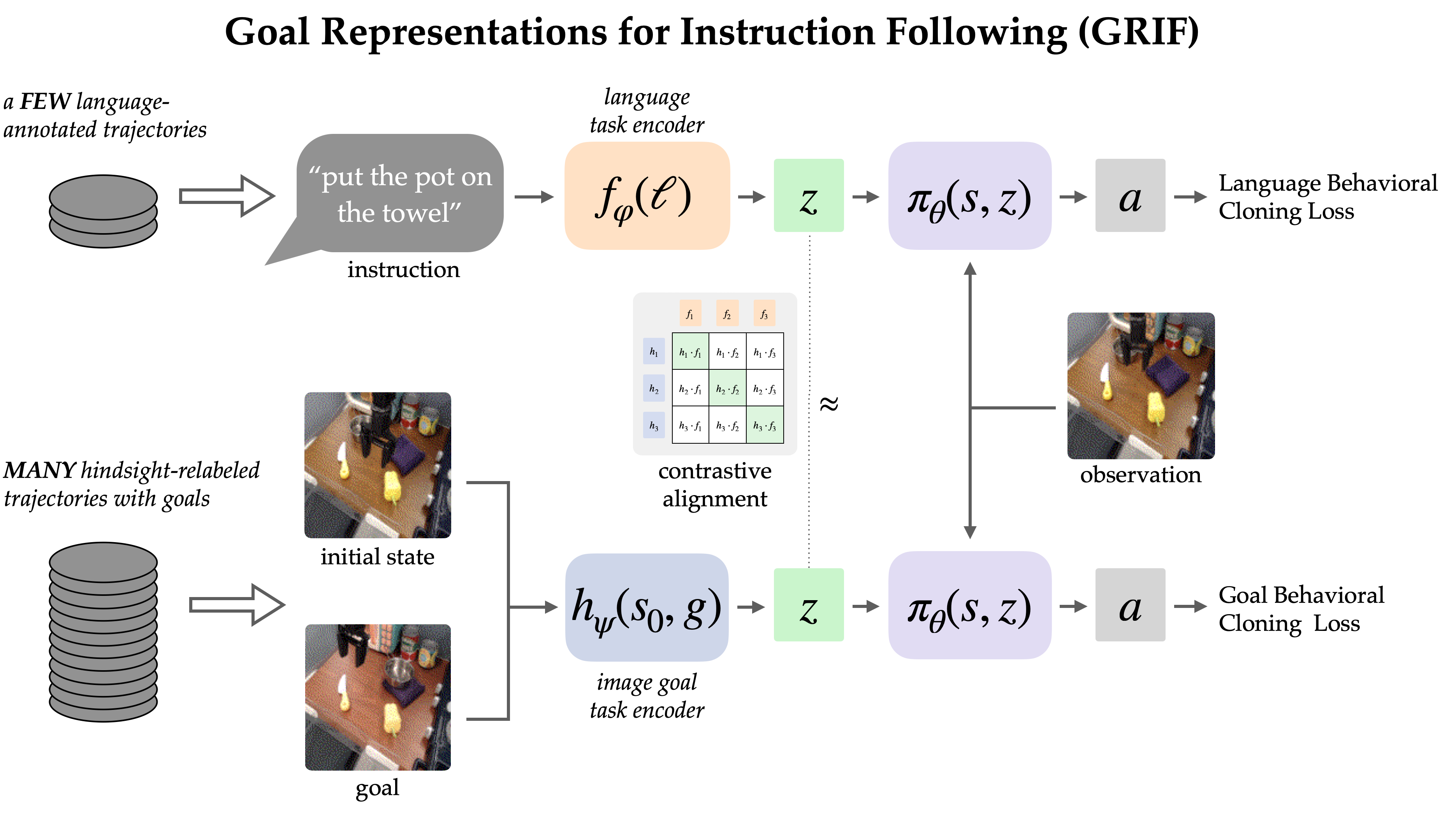

The GRIF model consists of a language encoder, a goal encoder, and a policy network. The encoders respectively map language instructions and goal images into a shared task representation space, which conditions the policy network when predicting actions. The model can effectively be conditioned on either language instructions or goal images to predict actions, but we are primarily using goal-conditioned training as a way to improve the language-conditioned use case.

Our approach, Goal Representations for Instruction Following (GRIF), jointly trains a language- and a goal- conditioned policy with aligned task representations. Our key insight is that these representations, aligned across language and goal modalities, enable us to effectively combine the benefits of goal-conditioned learning with a language-conditioned policy. The learned policies are then able to generalize across language and scenes after training on mostly unlabeled demonstration data.

We trained GRIF on a version of the Bridge-v2 dataset containing 7k labeled demonstration trajectories and 47k unlabeled ones within a kitchen manipulation setting. Since all the trajectories in this dataset had to be manually annotated by humans, being able to directly use the 47k trajectories without annotation significantly improves efficiency.

To learn from both types of data, GRIF is trained jointly with language-conditioned behavioral cloning (LCBC) and goal-conditioned behavioral cloning (GCBC). The labeled dataset contains both language and goal task specifications, so we use it to supervise both the language- and goal-conditioned predictions (i.e. LCBC and GCBC). The unlabeled dataset contains only goals and is used for GCBC. The difference between LCBC and GCBC is just a matter of selecting the task representation from the corresponding encoder, which is passed into a shared policy network to predict actions.

By sharing the policy network, we can expect some improvement from using the unlabeled dataset for goal-conditioned training. However,GRIF enables much stronger transfer between the two modalities by recognizing that some language instructions and goal images specify the same behavior. In particular, we exploit this structure by requiring that language- and goal- representations be similar for the same semantic task. Assuming this structure holds, unlabeled data can also benefit the language-conditioned policy since the goal representation approximates that of the missing instruction.

Alignment through Contrastive Learning

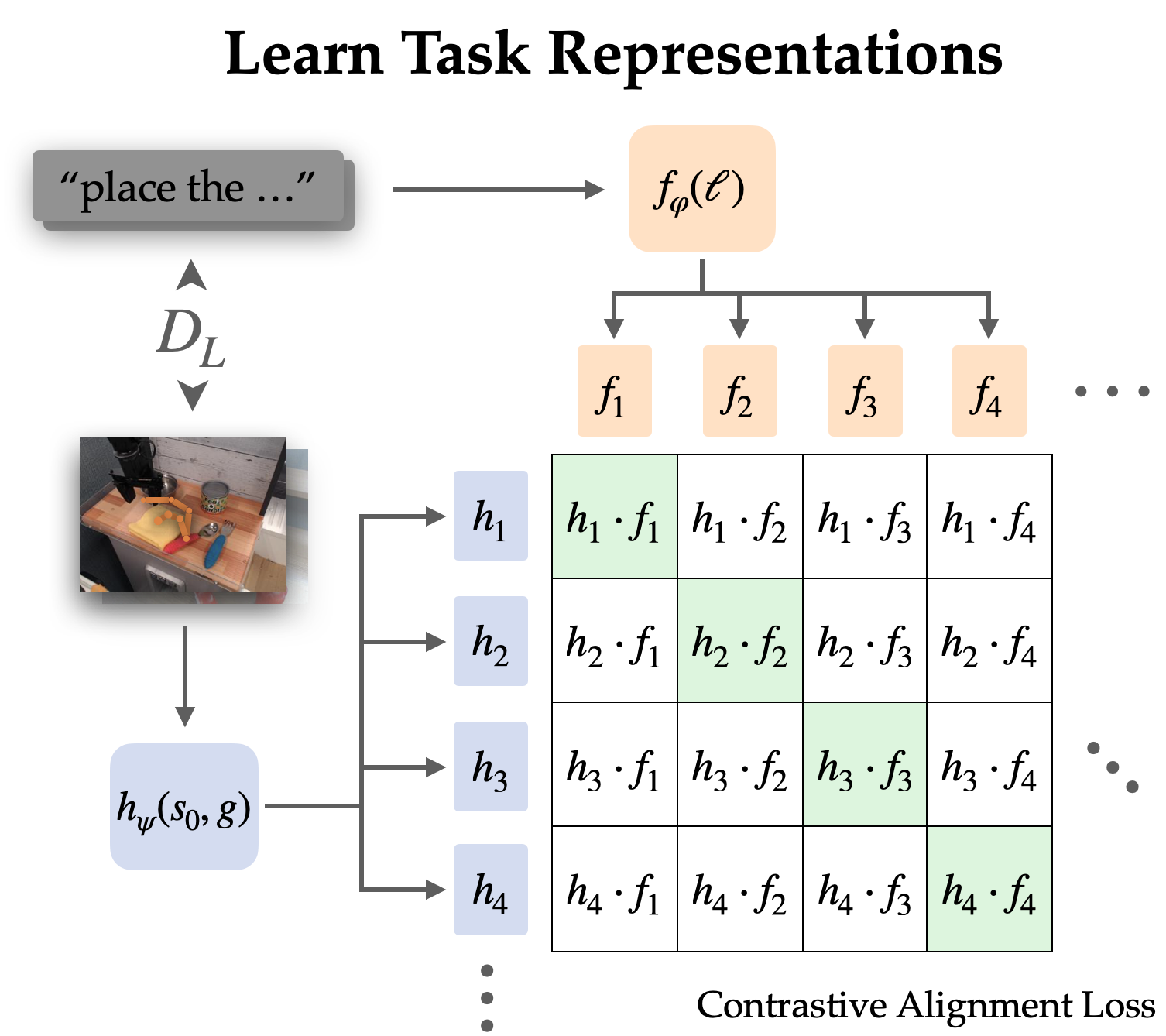

We explicitly align representations between goal-conditioned and language-conditioned tasks on the labeled dataset through contrastive learning.

Since language often describes relative change, we choose to align representations of state-goal pairs with the language instruction (as opposed to just goal with language). Empirically, this also makes the representations easier to learn since they can omit most information in the images and focus on the change from state to goal.

We learn this alignment structure through an infoNCE objective on instructions and images from the labeled dataset. We train dual image and text encoders by doing contrastive learning on matching pairs of language and goal representations. The objective encourages high similarity between representations of the same task and low similarity for others, where the negative examples are sampled from other trajectories.

When using naive negative sampling (uniform from the rest of the dataset), the learned representations often ignored the actual task and simply aligned instructions and goals that referred to the same scenes. To use the policy in the real world, it is not very useful to associate language with a scene; rather we need it to disambiguate between different tasks in the same scene. Thus, we use a hard negative sampling strategy, where up to half the negatives are sampled from different trajectories in the same scene.

Naturally, this contrastive learning setup teases at pre-trained vision-language models like CLIP. They demonstrate effective zero-shot and few-shot generalization capability for vision-language tasks, and offer a way to incorporate knowledge from internet-scale pre-training. However, most vision-language models are designed for aligning a single static image with its caption without the ability to understand changes in the environment, and they perform poorly when having to pay attention to a single object in cluttered scenes.

To address these issues, we devise a mechanism to accommodate and fine-tune CLIP for aligning task representations. We modify the CLIP architecture so that it can operate on a pair of images combined with early fusion (stacked channel-wise). This turns out to be a capable initialization for encoding pairs of state and goal images, and one which is particularly good at preserving the pre-training benefits from CLIP.

Robot Policy Results

For our main result, we evaluate the GRIF policy in the real world on 15 tasks across 3 scenes. The instructions are chosen to be a mix of ones that are well-represented in the training data and novel ones that require some degree of compositional generalization. One of the scenes also features an unseen combination of objects.

We compare GRIF against plain LCBC and stronger baselines inspired by prior work like LangLfP and BC-Z. LLfP corresponds to jointly training with LCBC and GCBC. BC-Z is an adaptation of the namesake method to our setting, where we train on LCBC, GCBC, and a simple alignment term. It optimizes the cosine distance loss between the task representations and does not use image-language pre-training.

The policies were susceptible to two main failure modes. They can fail to understand the language instruction, which results in them attempting another task or performing no useful actions at all. When language grounding is not robust, policies might even start an unintended task after having done the right task, since the original instruction is out of context.

Examples of grounding failures

“put the mushroom in the metal pot”

“put the spoon on the towel”

“put the yellow bell pepper on the cloth”

“put the yellow bell pepper on the cloth”

The other failure mode is failing to manipulate objects. This can be due to missing a grasp, moving imprecisely, or releasing objects at the incorrect time. We note that these are not inherent shortcomings of the robot setup, as a GCBC policy trained on the entire dataset can consistently succeed in manipulation. Rather, this failure mode generally indicates an ineffectiveness in leveraging goal-conditioned data.

Examples of manipulation failures

“move the bell pepper to the left of the table”

“put the bell pepper in the pan”

“move the towel next to the microwave”

Comparing the baselines, they each suffered from these two failure modes to different extents. LCBC relies solely on the small labeled trajectory dataset, and its poor manipulation capability prevents it from completing any tasks. LLfP jointly trains the policy on labeled and unlabeled data and shows significantly improved manipulation capability from LCBC. It achieves reasonable success rates for common instructions, but fails to ground more complex instructions. BC-Z’s alignment strategy also improves manipulation capability, likely because alignment improves the transfer between modalities. However, without external vision-language data sources, it still struggles to generalize to new instructions.

GRIF shows the best generalization while also having strong manipulation capabilities. It is able to ground the language instructions and carry out the task even when many distinct tasks are possible in the scene. We show some rollouts and the corresponding instructions below.

Policy Rollouts from GRIF

“move the pan to the front”

“put the bell pepper in the pan”

“put the knife on the purple cloth”

“put the spoon on the towel”

Conclusion

GRIF enables a robot to utilize large amounts of unlabeled trajectory data to learn goal-conditioned policies, while providing a “language interface” to these policies via aligned language-goal task representations. In contrast to prior language-image alignment methods, our representations align changes in state to language, which we show leads to significant improvements over standard CLIP-style image-language alignment objectives. Our experiments demonstrate that our approach can effectively leverage unlabeled robotic trajectories, with large improvements in performance over baselines and methods that only use the language-annotated data

Our method has a number of limitations that could be addressed in future work. GRIF is not well-suited for tasks where instructions say more about how to do the task than what to do (e.g., “pour the water slowly”)—such qualitative instructions might require other types of alignment losses that consider the intermediate steps of task execution. GRIF also assumes that all language grounding comes from the portion of our dataset that is fully annotated or a pre-trained VLM. An exciting direction for future work would be to extend our alignment loss to utilize human video data to learn rich semantics from Internet-scale data. Such an approach could then use this data to improve grounding on language outside the robot dataset and enable broadly generalizable robot policies that can follow user instructions.

This post is based on the following paper:

If GRIF inspires your work, please cite it with:

@inproceedings{myers2023goal,

title={Goal Representations for Instruction Following: A Semi-Supervised Language Interface to Control},

author={Vivek Myers and Andre He and Kuan Fang and Homer Walke and Philippe Hansen-Estruch and Ching-An Cheng and Mihai Jalobeanu and Andrey Kolobov and Anca Dragan and Sergey Levine},

booktitle={Conference on Robot Learning},

year={2023},

}

[ad_2]